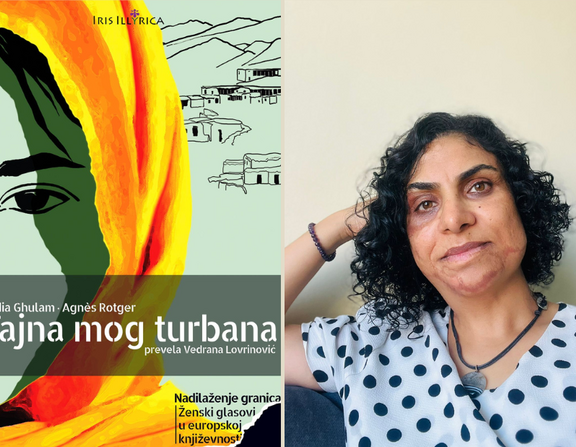

Photo: Nadia Ghulam.

This year, the Festival of World Literature is welcoming numerous intriguing names, among them the Afghan-Catalan author Nadia Ghulam. Nadia is an activist, educator, and human rights advocate, whose courage, resourcefulness, and unbreakable spirit have captivated readers across the globe. In her autobiographical story The Secret of My Turban (Iris Illyrica, 2024), she shares her personal experiences of fighting for freedom and human rights with honesty and without reservation, while also revealing the challenges of growing up amid extreme injustice and violence.

Nadia experienced great losses in Afghanistan due to the civil war, famine, and the Taliban regime. In collaboration with journalist Agnès Rotger, she wrote the novel The Secret of My Turban (El secret del meu turbant, 2010), which chronicles ten years she spent in Afghanistan disguised as a man in order to work and support her family, as even that was forbidden for women under Taliban rule. Despite these hardships, the book inquisitively explores her relationship with the world, her identity, religion, and her connections with others. She resists sentimentality and, as a girl and young woman, boldly writes about topics considered scandalous by the regime, such as love and female sexuality.

As the founder of the non-governmental organization Ponts per la Pau (Bridges of Peace) in Catalonia, Nadia is passionately dedicated to empowering Afghan women and girls through unique educational programs, while also facilitating the integration of migrants in Catalonia. Her dedication to the rights of women and migrants has earned her numerous awards in the field of social activism.

The Secret of My Turban is her first book translated into Croatian (translated by Vedrana Lovrinović). Completely captivated by this book, I couldn’t miss the opportunity to talk with Nadia. In our pleasant conversation, we covered numerous topics, from her deep motivation for writing this book, the unusual process of collaborative writing in a foreign language, her dedicated fight for the rights of women and migrants, to the importance of storytelling.

What inspired you to write the book and translate your experience into text?

While living in Afghanistan, I was often interviewed by journalists from around the world. To them, my story—a girl dressing as a man—was unique and made for a very good headline. But, once the interviews were over, they no longer cared about me, my story, or the situation of my family. This deeply hurt me, when people show interest in a difficult situation only to take what they need and then get lost forever. When I arrived in Spain, it was very clear that my story needed to come out. I realized that even if I didn’t write it myself, my story would still be out there, often in articles or books where people had taken the liberty to invent or twist it. I wanted to be the owner of my story, to tell it in my own words, and not let others take that from me. That’s why I decided to write a book.

What challenges did you face in telling your story from a first-person perspective? Autobiographical books deal with confronting the past, and everyone has a different process for handling and writing about it.

The most important challenge was to go through that pain and those difficulties—going back to the trauma. Revisiting trauma isn’t just about remembering it; it’s like experiencing it all over again, and that was very hard for me. It was also a difficult time because I was in Spain, facing new challenges. I was back in the hospital for my injuries, which reopened not only my physical injuries but also my emotional ones. Being far away from my mother and family made it even harder. I also worried about whether people would understand what I wanted to say. Sometimes, when you’re explaining something deeply important to you, it might seem like just a sentence, a comment, or a book to someone another person. I didn’t want that to happen. I wanted my words to reach the hearts of my readers. Through this book, I wanted to make readers conscious of how war destroys lives.

And I think you've succeeded in that. Did you have a clear voice and message you wanted to convey from the start, or did it develop and become stronger over time?

I was very clear from the beginning about what I wanted to explain. When young adults read my books in school, they often ask how I remember such small details. I tell them it's because those experiences were very hard for me. The difficult things will not forget you—they’re written in your heart, etched by the pain, anger, sadness, and everything you go through. My Afghan mother found it curious that I remember so many details from my early childhood, but I do. I remember every single thing. So, I knew exactly what I wanted to explain and how I wanted to do it. This is not my art; it’s the art I inherited from my mother. She was an excellent storyteller, and she couldn’t read or write, but her storytelling was exceptional, and I believe that art came from her.

If I'm not mistaken, you also wrote a book about the stories your mother told you?

Yes, I now have seven books, three of which are collections of tales. One is a collection of the stories my mother shared with me.

One of the key issues you explore in The Secret of My Turban is the question of identity. I’m curious about how the experience of migration influenced your perception of identity and how that reflects in your literary work?

When I arrived in Spain, my perspective on men and women was completely different from what I had known. It had no similarity. In Afghanistan, men could do everything, and women cannot. However, as I lived in Spain, I slowly realized that as a woman, I could do all the things I did as a man in Afghanistan—like riding a bicycle, having friends, walking alone on the street, or hiking in the mountains. Nothing bad would happen. Once I arrived in Spain and began writing the book, I conveyed the truth of my life in Afghanistan.

You speak multiple languages and this novel was written in Catalan. How did you approach writing in a language that isn’t your mother tongue?

It's four hands writing; I co-wrote it with another journalist who is Catalan. Since the book is autobiographical, if I didn’t have the exact words or expressions I needed, I would use theater to communicate. Through nonverbal language, I could convey what I meant: we would sit on the ground without tables or chairs, eating with our hands. I wanted to explain everything. Sometimes, the journalist would try to make the text more literary beautiful, but I insisted, "No, I don’t want it to be literally beautiful; I want it to be my story."

For instance, I remember describing my mother’s room, saying the curtains were red and the mattresses were also red. When she sent me the text, I read it with my Catalan father, and she had written that the curtain color matched the wall, not the mattresses. I said, "No, Papa, it’s not true. It matched the mattresses." He told me: "Nadia, don't be like this. Just leave it. It is not very important. The wall or the mattresses are not so important. Why do you want to change everything?" I answered: "Papa, I don't want it to be literally beautiful. I want it to be my story." So I rejected the text again and said to her that she didn’t understand. She had to read it and had to rewrite it.

It was challenging because rejecting someone’s hard work isn’t easy. It’s like you writing this article, and I told you tomorrow that it’s not right and you need to start over. It took courage from me to insist on my story, and a lot of effort from her to start again. For me, that moment was very difficult because I didn’t have enough courage, but I was still fighting for courage.

How long was the process?

It took two years, we met two or three times a week for a few hours each time.

I would also like to know, how did you manage to reconcile your Afghan and Catalan identities, or more precisely, your linguistic identity when writing?

It was largely thanks to my Catalan family. I have a wonderful Catalan family—my father and uncle were both deeply involved with Middle Eastern literature. My Catalan father was a doctor, but his brother was a philologist specializing in the Catalan language. They always encouraged me to express myself, even in a language that wasn’t my own, and they would correct me when necessary. They never told me to abandon my language or culture. Instead, they would point out similarities between languages and cultures. For example, I remember my uncle, who was a great writer in Catalonia, showing me how in my language, we say "mother", and in German, they also say "mother". He always emphasized the importance of maintaining your own language and culture, even when living in a different place. They taught me that knowing both languages and cultures makes you richer.

Speaking of multilingualism, many people I talk to use different languages for different functions. For example, they use one language with friends, another at work, in one they reflect on everyday life, and then translate it. I'm always interested to hear that: what language do you dream in?

I dream in Catalan because it is my second mother tongue. Since I arrived in Catalonia, I’ve been surrounded by a Catalan family. Although I can speak my own language, I know a lot of details about it, I cannot grammatically analyze sentences. But in Catalan, I can do that. So, when I dream, I dream in Catalan, and then I translate those dreams into other languages I know.

Your book has been translated into sixteen languages, and it’s read by people all over the world. Here in Croatia, readers were excited about your visit and the opportunity to see you at the Festival of World Literature. What kind of reactions do you receive from readers? Are there any comments or messages that have particularly stayed with you?

It’s so amazing because I have people that are writing to me: "I read your book in one night!" I think, "Oh my god, I can’t even read a book in one night!" They’re such dedicated readers, and I receive very beautiful messages. For example, a girl from Germany, who now follows me on Instagram, is one of those readers. She connects with me deeply on an emotional level, even though we’ve never met. When we talk, it feels like an old friend is writing to me, even though I can’t even pronounce her name in German. Lots of people with a lot of love. I’ve received so many messages over the years, a lot of support from readers all around the world.

In 2010, you received the Prudenci Bertrana Award for this book, a significant prize for works written in Catalan. After The Secret of My Turban and several other books, how do you see your place in Catalan literature today? Do you see yourself alongside other Catalan writers?

I don't consider myself a writer; I’ve always said that I’m more of a very good storyteller than a writer. There are many great Catalan writers, like my uncle, Joan Soler i Amigó, who was very famous in Catalonia. He appreciated my work, my texts, and was always in love with what I was saying. For me, he was the best, and the fact that he valued my work meant a lot. Many people in Catalonia love me and consider me a writer, but I see myself more as a storyteller—an art I inherited from my Afghan mother.

As I mentioned, the book has been translated into sixteen languages, and the German translation was nominated for the Deutscher Jugendliteratur Preis. You’ve spoken about it on various occasions, and I imagine you’ve had many different experiences with it. After such a long journey with this book, when you look back, how do you view it today?

Unfortunately, and sadly, I see it as a classic account of human destruction in the world—of war and all its consequences. When I read books like The Diary of Anne Frank or The Boy in the Striped Pajamas, which is another story about the Second World War, I see many similarities with my own story. These books are from many years ago, yet my book reflects that these traumas, this hard life, haven't ended. It’s very sad because, despite all the advancements humanity has made—we’ve even reached the moon to look for water—we still can't bring peace to our own planet. In fact, it's getting worse and worse.

When I see the ongoing conflicts—the refugee crisis, the wars in Palestine, Ukraine, in so many other countries in Africa, the increasing violence in Afghanistan, and the lack of opportunities for women who can’t go to school, speak publicly or sit down like you and me—it makes me very sad. What is going on in this world? I wish books like mine weren't neccessary and didn’t have to exist. But they do because people like me suffer. And I don’t want other people to suffer. I wrote this book with the hope that someone would read it and change things, but it often feels like we, humans, are not learning anything. Those in power, the ones making war, are perhaps not interested in reading books like mine.

Unfortunately, yes. But precisely in order to change things, you act as a strong advocate for the rights of women and migrants. Your organization, Ponts per la Pau (Bridges for Peace), focuses on the education of women and migrants. What motivates you in your activism?

I believe in civil society. I believe in people like you, the younger generation. If any of my words reach your heart and inspire you to create change in others' lives, that’s my activism. I can't change those who hold power, but civil society can make a difference. I work with people to help them realize that they have rights and that even small actions can create change. You might not be able to change the lives of all migrants, but by simply looking into the eyes of your neighbours that you have around you and saying, "Good morning", you’re making a big change in humanity.

You mentioned that you consider yourself a storyteller. What does the power of storytelling mean to you today?

Today, storytelling is more important than ever. With AI technologies like ChatGPT, anyone can write anything, even if it's fake. That's why people who have truly suffered or have real stories to tell must be empowered to share them. Our stories need to be heard by society because, otherwise, everything risks becoming fake. I'm a testimony to the violence against women in Afghanistan. I’m the testimony of the lack of freedom. I have to speak up so people can see that these issues exist. Otherwise, it’s like we’re living in a fictional world, where everything is created by artificial intelligence or exists only in movies. But these issues are real. We are not YouTubers or activists seeking fame.

I’ve suffered, and I want to speak out to show that this suffering is real. I’m not doing this for fame or money. I speak out because there are many good people who feel helpless, who think they can’t do anything. I’m here to tell them that they can make a difference. Look at my Catalan family—they gave me the opportunity to get an education, and now I’m not only a role model for people in my country but also for other Afghan girls who now have no freedom in Afghanistan now.

In my program, I work with 550 women who share with me their struggles—how they suffer from not being able to go to school. How they’re suffering from the lack of freedom. I understand them, and I share with them my stories, what I felt during those times and how I managed to escape the darkness. Because if you say "yeah, I understand you", they will say, "no, you will never understand me. You never had this life. You don't know what this means, to be without freedom". But with me, they can’t say that because I’ve experienced hunger, war, injuries, hospital stays, lack of medicine, lack of freedom—everything. I understand their pain, and then they understand how hard work and believing in yourself can change your life.

Yes, it is invaluable to be able to provide them with deep empathy in those moments. While you were talking, I thought about some women I’ve spoken with who’ve read your book. They all said things like, "She’s so courageous, so inspirational. I couldn’t believe how this book moved me—I couldn’t stop reading it." Do you think we should be braver or more courageous in telling stories in literature in general?

We should be, but societies often pressure people to hide their emotions. When you express your emotions, they see it as a sign of weakness. But we shouldn’t wait for society to approve of us. We need to express what we feel. Some people might understand us; others might not. But that doesn’t mean we should hide our emotions. I always express my emotions, and some people say, "It’s therapy for you to talk about your emotions." But it’s not therapy. Every time I talk about my life, I relive those stories, and it hurts. But I share them because I know there are many other women who are suffering, and they don’t speak up because they’re afraid of being judged, misunderstood, or laughed at.

I’ve met many Afghan refugee women who’ve gone through anger and various types of violence. When we sit at the same table, I talk very freely about my experiences—how I had no water for days and how happy I am to have water now in front of me. For them, it’s like they want to say, "I had the same experience," but they hold back and instead say, "Yeah, there are people who are suffering." No, you have to explain who you are.

I think in Spain, for example, the younger generation is losing the ability to express emotions. It’s all about Instagram and showing the happiest moments—good coffee, good parks, good views, and so on. But that’s not real life. When I lost my father, I tried to express all my emotions on Instagram. Some friends asked, "Nadia, is it correct to do that?" I said, "Yes, of course, because social media shouldn’t be all fake. It should be real, showing how I feel." I felt said, so I put it there. Social media is a powerful tool if we use it honestly. Unfortunately, many people today are losing that honesty. They feel like if they post something real, they won’t get enough likes or comments. But I don’t care about that. This is who I am, and I express myself honestly. Some people will respond positively, others might ignore it. I don’t mind. We need to use every tool we have in our lives for good.

Are you writing anything these days? Are you in the process of working on something?

What’s on my mind is writing a book about my relationship with my Catalan father. I have a lot of letters from him, and I want to create a conversation between him and me. It’s in my mind, but right now, I’m feeling too sad to sit down and start writing. Hopefully, I’ll find the courage to do it.