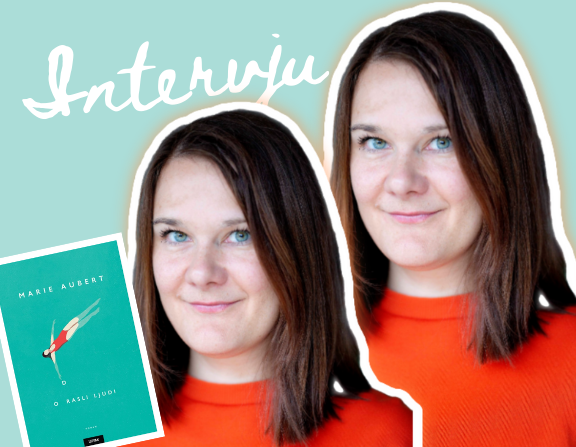

An interview with Norvegian writer Marie Aubert about her novel Grown Ups (Odrasli ljudi, Naklada Ljevak 2021). Questions by Ivana Drazic.

So far you have published two books, a novel "Grown Ups" and the debutant book of short stories "Can I come home with you". "Grown Ups" is also a book by which Croatian readers get to know you. Aside from the fact that he you write prose - what else is important to know about Marie Aubert?

I live in Oslo, Norway, I have previously worked as a journalist and with PR relations, but at the moment, I’m a full time writer. Right now I’m working on my third book.

It seems to me that the (anti)heroine of this novel, Ida, is really lonely. She tries to cure loneliness by finding a partner, having short-term relationships, and ultimately by wanting to have a child, at the „last minute”, as it seems to her. Do you think loneliness is the true symptom of adulthood (being a „grown up”)? Do you think that we are all a bit lonely (even when it doesn’t seem like it at first, like Marthe and Kristoffer’s relationship)?

I think that most of what I write circles around how we attempt to get close to other people, and how we often fail along the way. Grown Ups deals with the shameful feeling of not being loved, both the struggling to find a partner at a crucial point in your life, and the deeper, existensial aspect of it.

Honestly, it was hard for me to sympathize with Ida, there is something deeply unlikeable in her that, even according to the Internet, most readers notice. And although the story is given from her perspective and some compassion is probably desirable, I did not feel it, primarily because of her actions that are often directed only at herself, her selfishness, irritation with others for no clear reason, etc. In general, it seems to me that no character in the novel is particularly likable, which is a real refreshment in literature (and art in general), that we can write and read female characters who do not try to please anyone or justify their actions to anyone, even readers. Why were characters like this interesting to you? Is it time for heroines of different kind?

Both readers and critics feel strongly about Ida - they either sympathize with her and recognize a lot of their own conflicted feelings in her, or they feel appalled. For me, it’s a good sign that she is a complex character that is hard to pin down easily. I don’t think Ida is a bad person, she does care about her family and she wants what most of us want. But she is at a vulnerable point in her life, she feels lonely and unloved, and gets completely overthrown by her own jealousy and resentment, to the point where any good intentions are no longer in control. I’m not drawn to writing about characters that are entirely good people and just victims of their circumstances, nor am I interested in writing about psychopaths who don’t care about anyone else. I like to write about people that are both good and bad, people who are torn between how they want to be and how they actually respond when they are pushed into a corner and feel threatened. And I think most of us from time to time find ourselves reacting in ways we are not proud of, especially when it comes to the ones we love the most. When we are very jealous or feel that we are about to lose something important, we are not the best versions of ourselves, but the ugly feelings are part of who we are, too - and to be able to deal with them, we have to get to know them. Female characters should not be expected to be “strong” or more wholesome just because they are women, they should be allowed to be just as flawed and contradictary as people generally are.

If it was not clear to the readers from the previous questions, this is a very character-oriented novel, and all the drama comes from the characters, from the tension of the title "Grown Ups” and characters who act like everyone but grown ups. How was it for you to write them? I often ask this in interviews, because I am very interested in whether writers sympathize with their characters. Do you sympathize with your own? Did you even want to evoke empathy for Ida in the reader?

I might have answered some of this in the previous question, but character building is probably the most important thing I do. When I write, I try to get into what this character feels strongly about, what they are ashamed of and how they try to hide it, and how they feel inferior or superior to other people. Rather than simply rooting for or sympathizing with one character, I like when the readers feel invested in the characters. That they somehow can feel what the characters feel, and at the same time shout within themselves “nooo, don’t do that, Ida!”

What is the reason you chose to thematize the relationship between sisters?

Sibling relations interest me because they are, for most of us, the longest relationships we will have throughout our lives, but at the same time, they are not relationships that we get to choose. When things go sour between siblings, it leaves you vulnerable because you know each other so closely. And there is often a competition aspect involved, even with siblings who get along well - the quest for being the more successful and more put together, the fight for parents’ approval and love. In some ways, sibling relations remains “childish” even when we grow up, because we often get stuck in the roles we had as children.

Given the theme of the novel and the way it is descibed in general, before reading it I imagined that the novel will have a strong feminist side, that it will articulate a criticism of society related to its main themes (women's reproductive health and rights, women's stories and major female characters) and I have to admit that, somewhere around the half of the novel, I noticed that all of this is missing (at least at first glance). Still, it seems to me that the novel can be read from a feminist perspective and a certain critique still exists. It is, I would say, most visible in criticizing the lack of any responsibility in men - they can cheat on women (but women are criticized when they are mistresses), they can decide they don't want children, they can just disappear and shift responsibility with almost no consequences. However, it is very subtle and is read between the lines. Why did you choose this, much more subtle approach?

I consider myself a feminist, but it’s not my intention to say something in general about male or female behaviour. Rather, I think the issues in the book deal with the difficult choices both men and women have to make as adults, and whether they really are conscious choices or not. However, I think that a female character who is single and childless in her forties is something that still diverges from the norm. Scandinavian countries are progressive and modern in lots of ways, but still homogenous, and the nuclear family is very deeply rooted in our society. I think that for many, it can still be quite hard not to be a part of a traditional family structure, and I think we need honest and complex stories from that perspective as well.

In one of the reviews (Borås Tidning, critics favorite), as well as in a few other comments I read that the book is "very Norwegian". What do you think that means? Is it because of the fjords and log cabins in the book or is it something else, some kind of objectively critical self-reflection? How to explain this to Croatian readers?

Some things in the novel are very Norwegian, indeed - for example, Norwegians are extremely invested in their cabins (“the hytte”), which often are more like well-equipped second houses than log cabins. Many of us have a cabin by the sea or in the mountains, and it’s considered perfectly normal to leave work early on Fridays to drive to the hytte before the weekend rush! Often, these cabins are inherited from parents or grandparents, and there are a lot of feelings and conflicts involved when it comes to which of the children will inherit the house, who has spent more time and money on it etc. - Another Norwegian aspect of the book is probably the understated style of prose, which I think I share with a lot of other Scandinavian writers.

The novel has an open ending. Is there a future where Marthe and Ida get along or one in which Ida is happy?

There might be. I wanted to leave Ida in a place and time where she can go in different directions, but where she, maybe for the first time, decides to be alone and find out where that leaves her. The sisters will still have a lot to figure out between them, but maybe they will find themselves and their relationship taking a more honest turn.

In the first question, I mentioned that you previously published a collection of short stories. How is writing a novel different from writing stories? In what aspects did you „let your imagination run wild”, as we like to say?

When you write a novel, you have endless possibilities, which is both fun and scary - you can include as many people as you want, write 100 or 800 pages, use a lot of backstory etc. Writing a short story leaves you with far less choices to make - you only have a few pages to tell your story, so you have to cut out everything that’s not important, you have to consider all time if this or that serves the story or not. I think it’s liberating to work within those limitations, too.